Hunter S. Thompson‘s article, ‘The Kentucky Derby Is Decadent and Depraved,’ launched his career as a Gonzo journalist and provided a spectacular caricature of a prestigious tradition.

But it is not an article about horse racing.

It’s about surviving crowds of drunkards, corruption and chaos.

More than that, it’s about being at the centre of that very crowd, while clinging to some paper and any mark-making instrument.

Published in Scanlan’s in June 1970, the story marked the beginning of Thompson’s Gonzo crusade. At the time of publication, he thought he had cooked his career and was entirely astounded by the public’s positive response – saying in an interview with Playboy, “It was like falling down an elevator shaft and landing in a pool full of mermaids.”

The article is made up of ten sections of memories and observations that trace Thompson’s (lack of) survival instincts as he spills through the Kentucky Derby – with all its colour, commotion and booze.

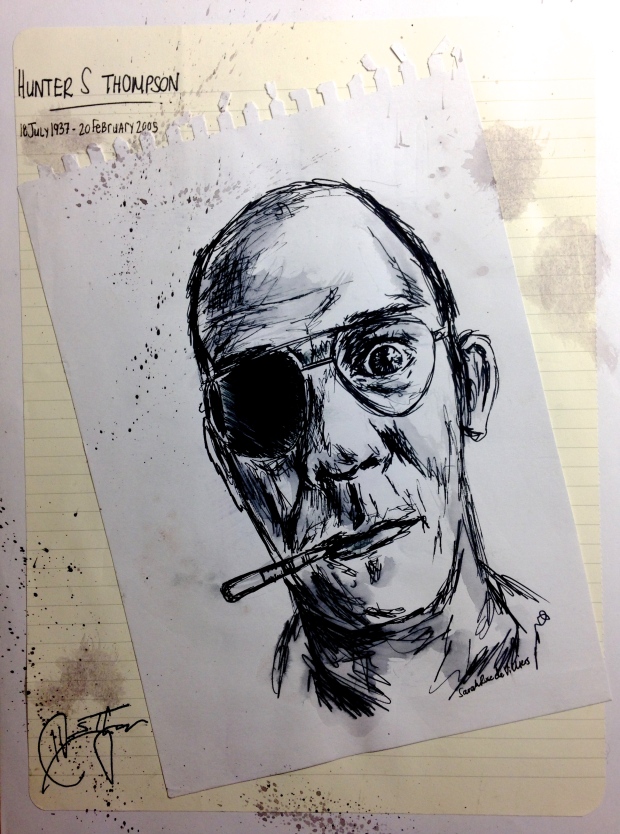

He lands in Kentucky with a bag that’s covered in baggage tags, and proceeds to put his charm, creativity and liver through every imaginable test. He manages to organise a can of mace, a hired car, two shabby rooms, press passes and an Irish partner-in-crime, Ralph Steadman – who does fabulously foul sketches that both insult the subjects and compliment a remarkably grotesque imagination.

Somehow, these two men make it through seas of drunken bodies, garbled conversations and retching characters, while sketching whiskered faces and scribbling notes in a red book that will – somehow – survive the entire ordeal and unravel the memories that would have otherwise been lost in the whirlwind of debauchery.

About half way through the article, Thompson gives this advice to Steadman:

“You should keep in mind that almost everybody you talk to from now on will be drunk. People who seem very pleasant at first might suddenly swing at you for no reason at all.”

He was speaking as much to Steadman as he was to the reader – for, be warned, the pleasantries of the introduction very quickly give way to the unrefined turmoil of absolute havoc.

The story opens with Thompson landing in Kentucky; it’s the sober starting block where the reeling adventure begins. Naturally, it’s followed by a scene at a bar, where he meet a character who embodies the excitement, sins and stereotypes of the Derby. In this way, the first paragraphs lay out the foundation, expectations and essence of the article – an offensive amount of money is going to be thrown into booze and bets, and conversations laced with wild ideas, whisky, and colourful characters.

For the remainder of the article, Thompson drags the reader through “a huge outdoor loony bin”, avoids crushing “a Volkswagon full of nuns” and then plunges into “a nightmare of mud and madness”. He focuses (I think this was when he was still sober enough to remember that he did, indeed, have a focus) on finding the face that was a “symbol… of the whole doomed atavistic culture that makes the Derby Day what it is”. He’s searching for “the mask of the whiskey gentry — a pretentious mix of booze, failed dreams and a terminal identity crisis; the inevitable result of too much inbreeding in a closed and ignorant culture.”

So he’s got a goal – of sorts – and proceeds to devoutly immerse himself in this culture and his search. Even if he doesn’t find the face, the description alone is enough to capture the corrupt decadence of the Derby, and his wonderful way with words.

His diction has the same sharpness of whisky’s scent; his imagery has the burning quality of swallowing bourbon and the metaphors are as horribly honest as a drunkard’s vomit. He’s not polishing reality, reserving judgment or dressing the scene in extravagance. He’s immersed, implicit and somewhat pissed.

He staggers from conversations, to contemplations, to motels and clubhouses. He sets the scene while describing the characters, carrying dialogue and critiquing the culture that underlies the entire experience. In this way, the story is constructed in the reader’s mind in much that same way that the memories are retrieved by Thompson – in fragments and flashes of details and interactions that are stirred into a story of extraordinary authenticity.

As spectacular as his contemplations and caricatures certainly are, they don’t even begin to match up to the magnificent spectacle of the central character: Thompson himself. His sense of humour and bizarre mannerisms make him the most twisted, fascinating and hilarious voice in the narrative. He writes with the same sincerely unapologetic honesty that characterises his interactions, and makes for wizard humour. This is especially evident in the section titled, “What Mace”:

“Look, Ralph,” I said. “Let’s not kid ourselves. That was a very horrible drawing you gave him. It was the face of a monster. It got on his nerves very badly.” I shrugged. “Why in the hell do you think we left the restaurant so fast?”

“I thought it was because of the Mace,” he said.

“What Mace?”

He grinned. “When you shot it at the headwaiter, don’t you remember?”

“Hell, that was nothing,” I said. “I missed him … and we were leaving, anyway.”

At this point, you’d think Thompson would reconsider, retract or retreat. Instead, he plunges the reader deeper into his disastrous dialogue and the scatterings of an eventful evening:

“But it got all over us,” [Steadman] said. “The room was full of that damn gas. Your brother was sneezing and his wife was crying. My eyes hurt for two hours. I couldn’t see to draw when we got back to the motel.”

“That’s right,” I said. “The stuff got on her leg, didn’t it?”

“She was angry,” he said.

“Yah … well, okay … let’s just figure we fucked up about equally on that one,” I said. “But from now on let’s try to be careful when we’re around people I know. You won’t sketch them and I won’t Mace them. We’ll just try to relax and get drunk.”

What they didn’t achieve in the former, they clearly achieved in the latter.

At the end of the weekend, Thompson finds the face that he had been looking for. It’s a frightful image: “a puffy, drink-ravaged, disease-ridden caricature … like an awful cartoon version of an old snapshot in some once-proud mother’s family photo album”. It’s his reflection. At the same time that he has been defeated by the week, he has also grabbed a double victory: he found the face, and was conscious enough to recognise it.

In the conclusion, Thompson returns to the airport once again. But instead of breathing hot air in quite darkness, he’s shoving a very battered illustrator out of a car that reeks of vomit, beer and mace. Despite having a hangover that would leave most people paralysed, he’s able to string together a cacophony of insults that could only be matched by the vulgarity of Steadman’s illustrations.

This story works as well as one of its drunken-stumbling characters. It doesn’t have the clean, cold and concise but edited effort of traditional journalism – it’s not an argument or arrangement of facts. Instead, it’s a twisted tale that jolts and jumps and swings from experience to memory to observation to telling reflections.

It’s a sensational slurring story that does the work of whisky and corrupt crowds, without the violent smells or shared sweat of complete and utter chaos.